It took almost 20 days, but the last state, Michigan, was finally called for Trump on Monday November 28th.

The final results of Election 2016 are now known:

Clinton 232 Trump 306, a 74 electoral vote win for Trump.

(That is absent faithless electors or something completely unexpected coming out of recounts of course.)

(UPDATE 2016-12-20 19:27 UTC: The electoral college has actually voted, and there were 7 faithless electors. The final count was Trump 304, Clinton 227, Others 7. This is a 77 electoral vote margin for Trump. For details, see my post titled “The Actual Presidential Vote“.)

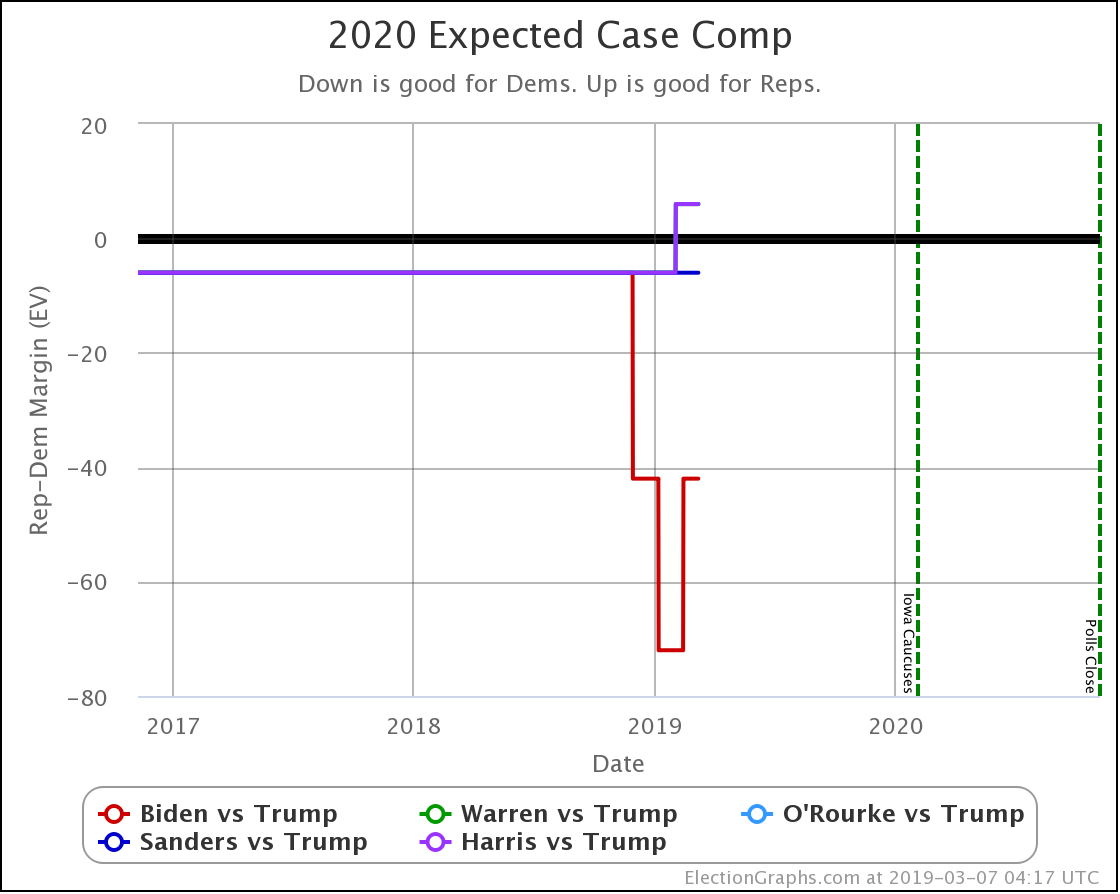

This site’s final update predicted that the result would be somewhere between a 210 electoral vote win for Clinton and a 66 electoral vote win for Trump, with the “expected” result being an 8 electoral vote win for Clinton.

Obviously I was wrong. Not just on the winner, but the result didn’t even come in within the “range of the reasonably possible” that I listed. A range which had seemed overly broad before the election. A 66 electoral vote win for Trump (or a 210 electoral vote win for Clinton) seemed like a complete fantasy. Yet Trump exceeded that margin.

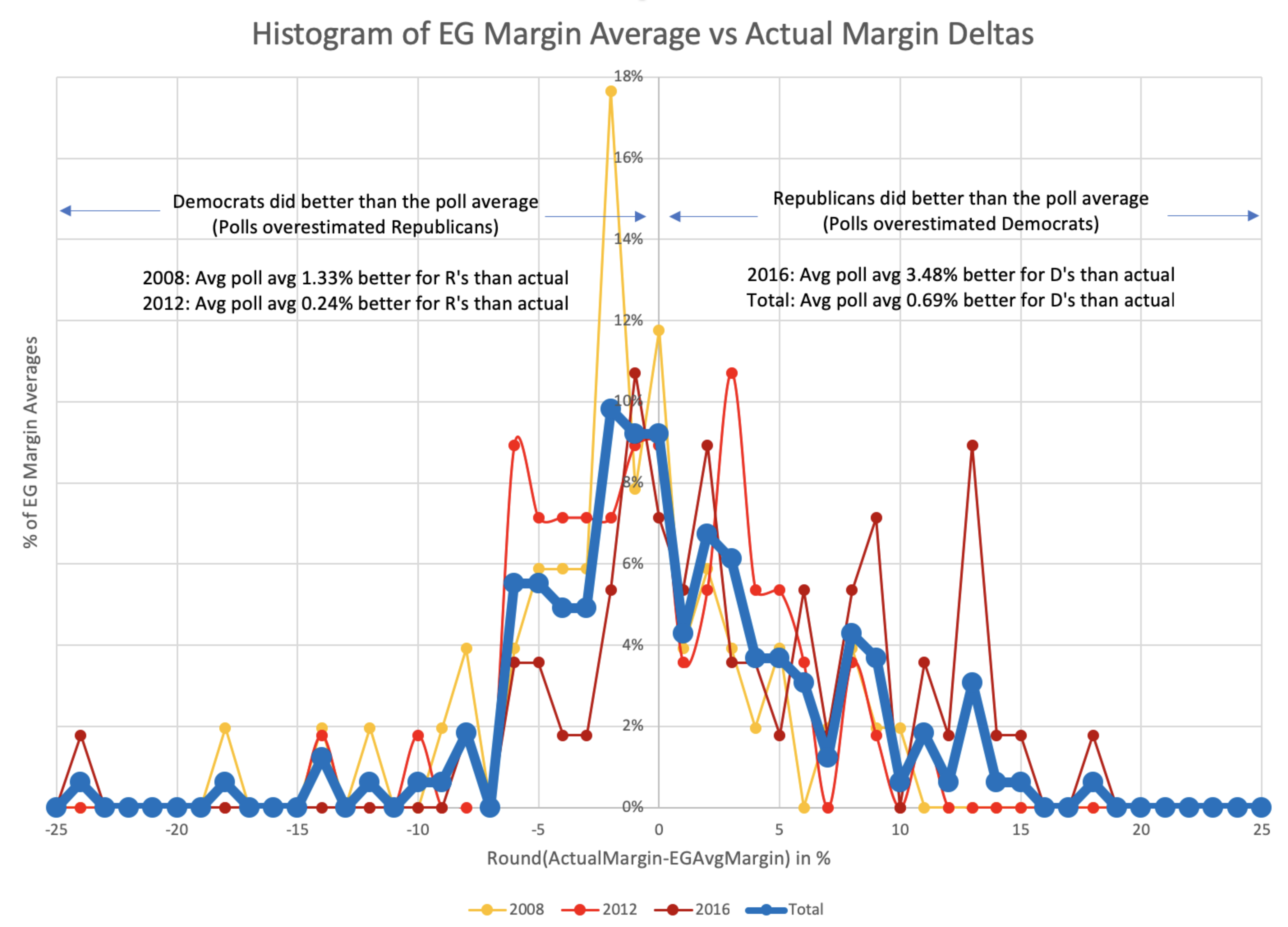

Having said that, the “expected result” was actually closer than almost all electoral vote trackers out there. So I actually did about as well as could have been done given the raw data that was available. So the raw output of my model on Election Graphs was pretty good. Perhaps I could have picked a bit wider window for the “swing” states than 5%, but 5% was generally reasonable. Although of course I wish I had gotten everything exactly right like I did in 2012, I am happy with how my model performed. I may make tweaks for 2020, but I will not dramatically change what I do with the model itself in 2020.

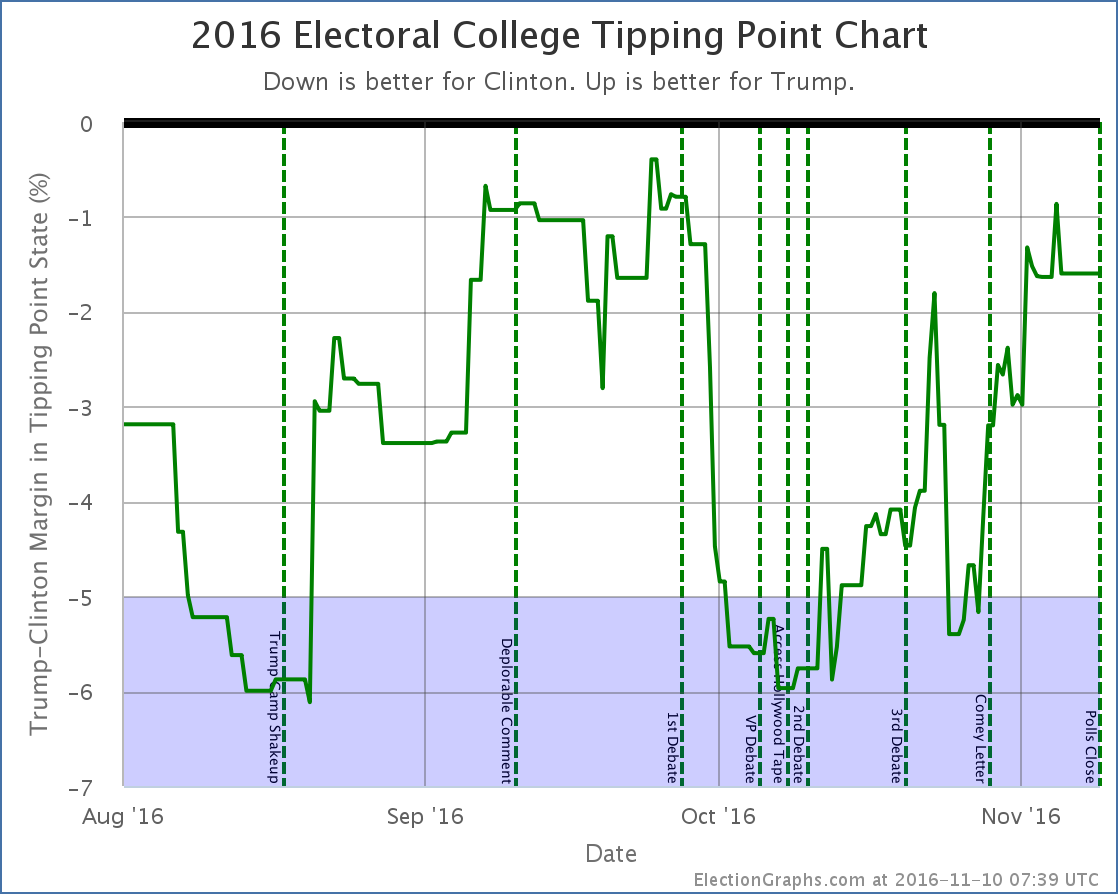

I do fault myself however for some of how I interpreted that data in my analysis posts, most critically I concentrated too much on the “Expected Case” and the “Tipping Point” metrics, and not enough on the full range of variation between the best cases. Like most electoral college trackers, this led me to minimize the chances of Trump’s win because “he has never led the race and isn’t ahead now” while essentially ignoring the fact that while that was true, he spent most of the last 100 days close enough that a systematic polling error or significant movement in the last few days could erase Clinton’s lead. Both seem to have happened. My model was spitting out the “Trump Best Case” the whole time, but for the most part, I downplayed the best cases. That was a mistake.

Lets dig in and look at the details.

Warning in advance, the remainder of this post is likely only to be of interest to “data geek” type folks. If that isn’t you, feel free to stop now… or just skip down to the “thank you” section at the end. If you are the data geek type, dive in with me to a lengthy discussion of the details and what lessons they may provide for 2020.

If you prefer listening to reading, or just want to hear about this in another way, I also discussed much of what I am now including in the post mortem in the November 11th episode of the Curmudgeon’s Corner podcast.

How did I do state by state?

In terms of individual states (and congressional districts), I of course did not match my 2012 record of getting 56 right out of 56. I ended up getting 5 wrong:

- Expected Strong Clinton: Wisconsin went for Trump instead of Clinton

- Expected Weak Clinton: Michigan went for Trump instead of Clinton

- Expected Weak Clinton: Maine CD2 went for Trump instead of Clinton

- Expected Weak Clinton: Pennsylvania went for Trump instead of Clinton

- Expected Weak Trump: Nevada went for Clinton instead of Trump

So there were 4 places where I erred toward Clinton and 1 where I erred toward Trump.

Of these, four were in the “weak” category, with margins in my averages of 2.6% or less. They were in my too close to call categories, and while I would have liked to have gotten more right, my model did indeed say they could easily go either way.

The only big surprise here was Wisconsin. The polling average had Clinton up by 7.1%, but Trump won anyway. There is nothing to say there other than the polling was way off in Wisconsin. Way off. I’m sure much will be written about why that was the case.

A state that I hadn’t even classified as a swing state going the opposite direction as expected is obviously how the final result was able to end up completely outside of the expected range. Wisconsin going for Trump was simply not contemplated. All the other states that went for Trump were within the range of options this site identified as plausible.

Of course, there were other states that I did not get wrong, but the margin was still off by more than expected. That is a different kind of analysis that I won’t do today.

How did I do on the overall result?

Looking at the over all electoral college result, lets compare with where some of the other sites had the race at the end:

First of all, I guess I am permitted to toot my own horn a bit. While I did not predict a Clinton victory, I came closer to the final result than all but one of the outlets above. That is something, right?

TOOT TOOT TOOT

That over with, I was still quite a ways off.

I should also point out that the above is ONLY due to changes added with polls that came out on the day before election day. My very last update on election day itself had the 8 EV Clinton margin. But the update before that, on Sunday, had me at 108 electoral votes, right there with so many others. Indeed, because I had been in broad agreement with so many other outlets, and my final update caused me to deviate quite a bit, I included caveats in my last update basically saying I didn’t believe it, there were probably outliers impacting the data, and my Sunday numbers were probably better.

Which brings me to the lessons of this post mortem…

Lessons

Trust my own method and data

Now, frankly, the swing on the last day may well have just been dumb luck. Random noise happening to go in the right direction. But it also could have been an indicator of the actual movement. Right or wrong, given I had been using a fixed methodology all election season, I should have stuck with it fully. After the election, if I was wrong, I could and should use that to learn for the next election cycle. But I started making excuses because I was not matching all the other election trackers. I should not have done this, I should have taken the results I was seeing seriously, and should have based my commentary on that.

My final update had an 8 EV Clinton win with a tipping point of only 1.6% in Pennsylvania. Only that one single state needed to flip in order for Trump to win. My final update did mention that Trump had made it tight again. I summed it up like this:

Maine CD2, Pennsylvania, Nevada, North Carolina, Florida, and Iowa are all within 2% at the moment. They could still go either way based on the current averages. That is enough to swing the election.

So, as has been the case for awhile, a Trump win would be surprising, but should not be shocking. Trump has a path.

Without looking at all the other forecasts and making excuses for why I was different, this should have read more like:

Maine CD2, Pennsylvania, Nevada, North Carolina, Florida, and Iowa are all within 2% at the moment. They could still go either way based on the current averages. That is enough to swing the election. Even more states are within 5%, and they could easily flip as well.

The tipping point is only 1.6% in Pennsylvania. Clinton’s lead in Michigan is also only 2.6%. A small last minute surge too late to be caught in polls, or a small polling error, could easily flip either or both of these states, and thus the election.

Clinton is ahead, she is the expected winner, but since early October things have been trending toward Trump, with only a brief interruption after the third debate and before the Comey letter.

The race is now very close. While Clinton is still favored, the bottom line is there is a reasonable chance this could go either way.

But I did not say that. And the reason was primarily because in that final update, I looked like an outlier, and I therefore didn’t believe what my own model said, specifically in terms of just how close it really was.

Which brings us to the next lesson.

Trust the Uncertainty

For the three election cycles I have done this, I have used a 5% margin as the boundary for what I call the “weak states”. States that you should consider to be too close to call and which could go either way. When justifying this, I have always said something like this:

Obviously 5% is an arbitrary number, which conveniently is a nice round number too, but between possible polling error, and possible last minute swings that happen to close to election day to be reflected in polls, 5% seems reasonable. A 5% last minute swing in response to news events is a bit large, but perfectly possible. Similarly a 5% polling error is a bit large, but possible. And my model only looks at the margin between the two major candidates, it does not explicitly account for the group of undecided voters, they could also possibly swing a result by that much in some cases. 5% seems as good a place to draw this line as any.

While having some sort of empirical way to define this line may be preferable, this election has shown that 5% is indeed pretty reasonable, and there are arguments that it should be even larger. (See Wisconsin again, which Trump won while my average had Clinton ahead by more than 7%.)

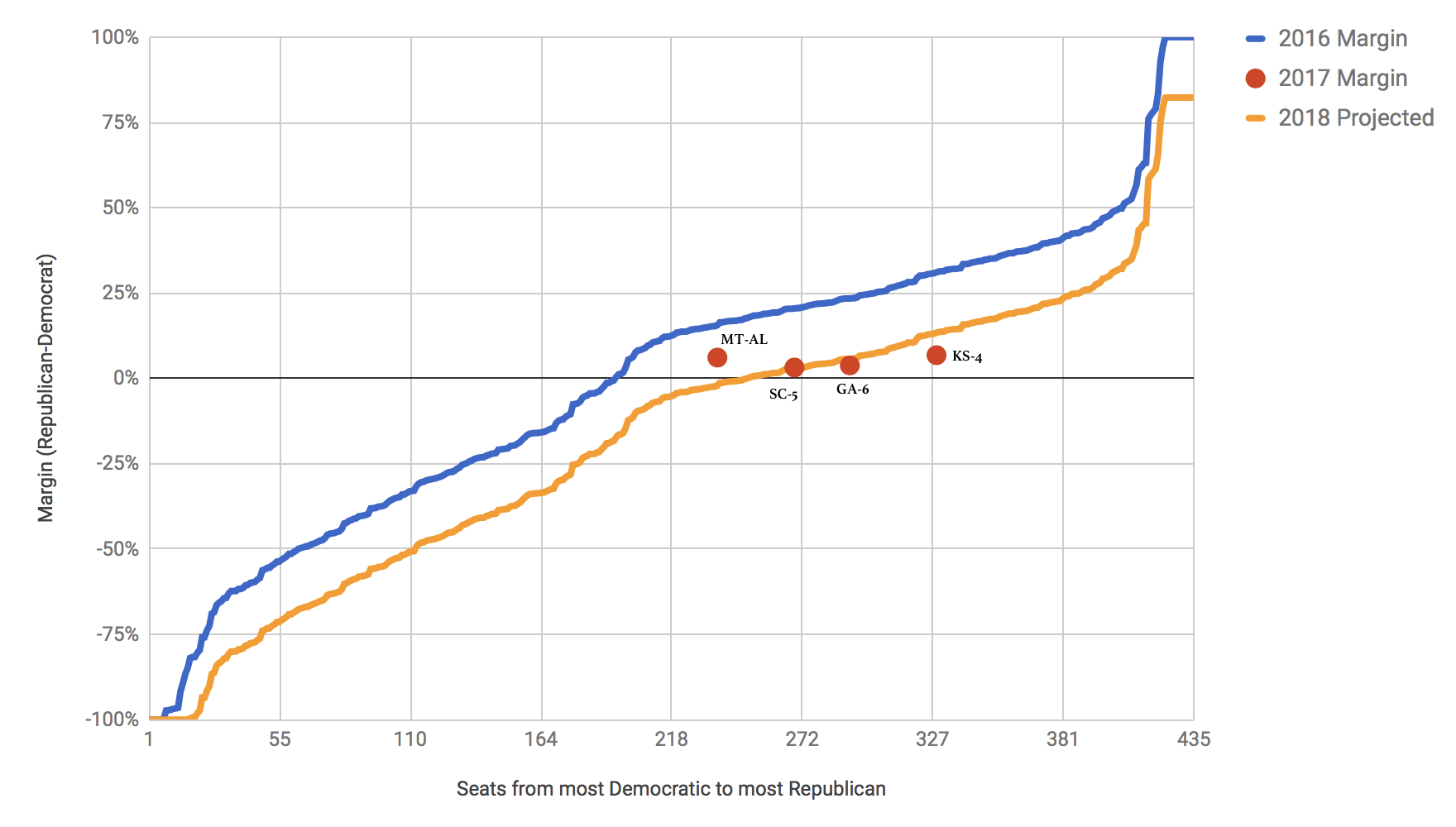

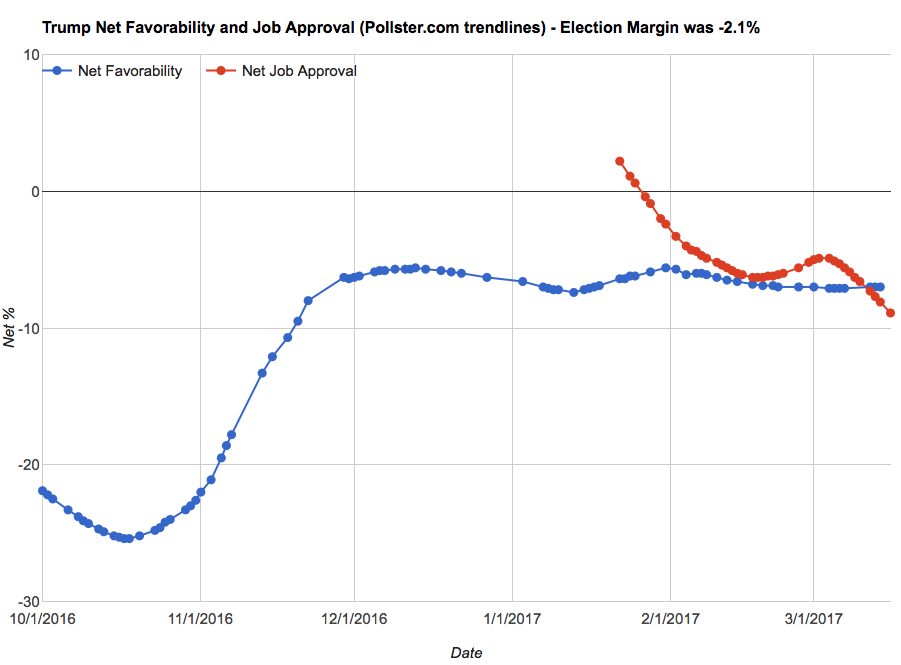

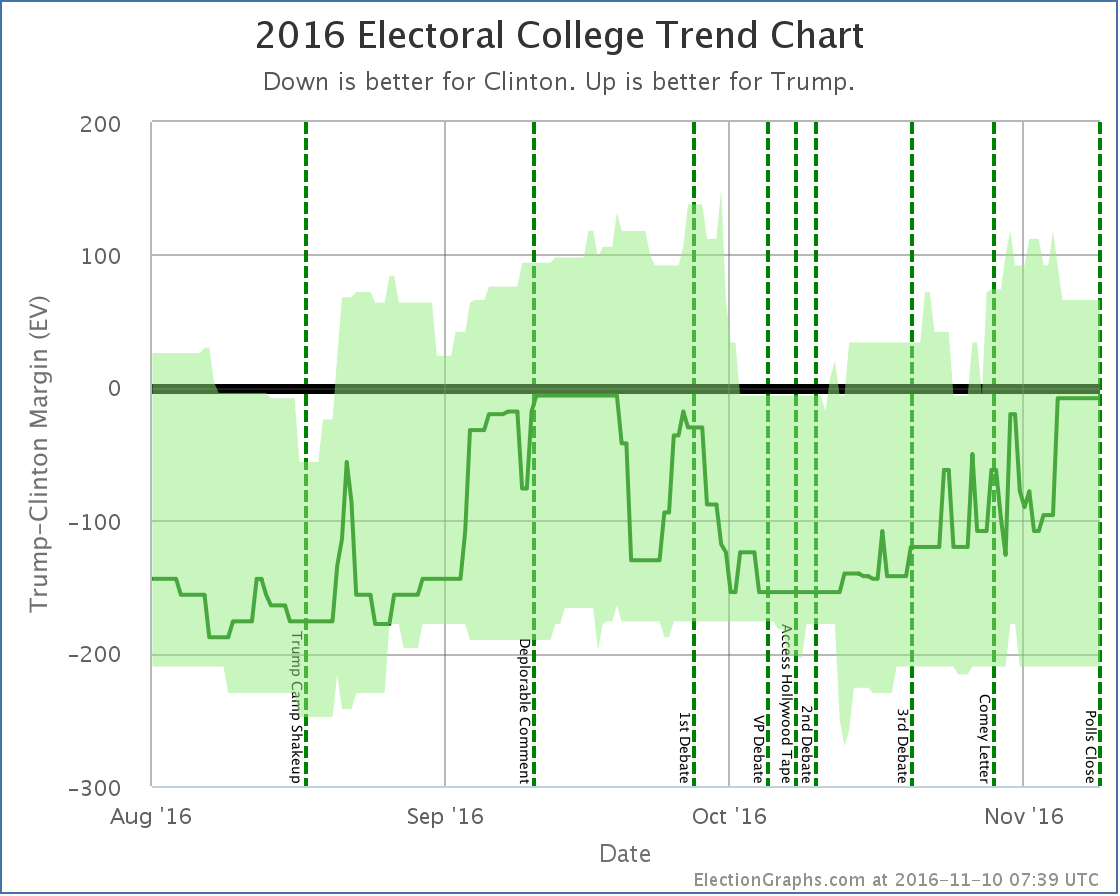

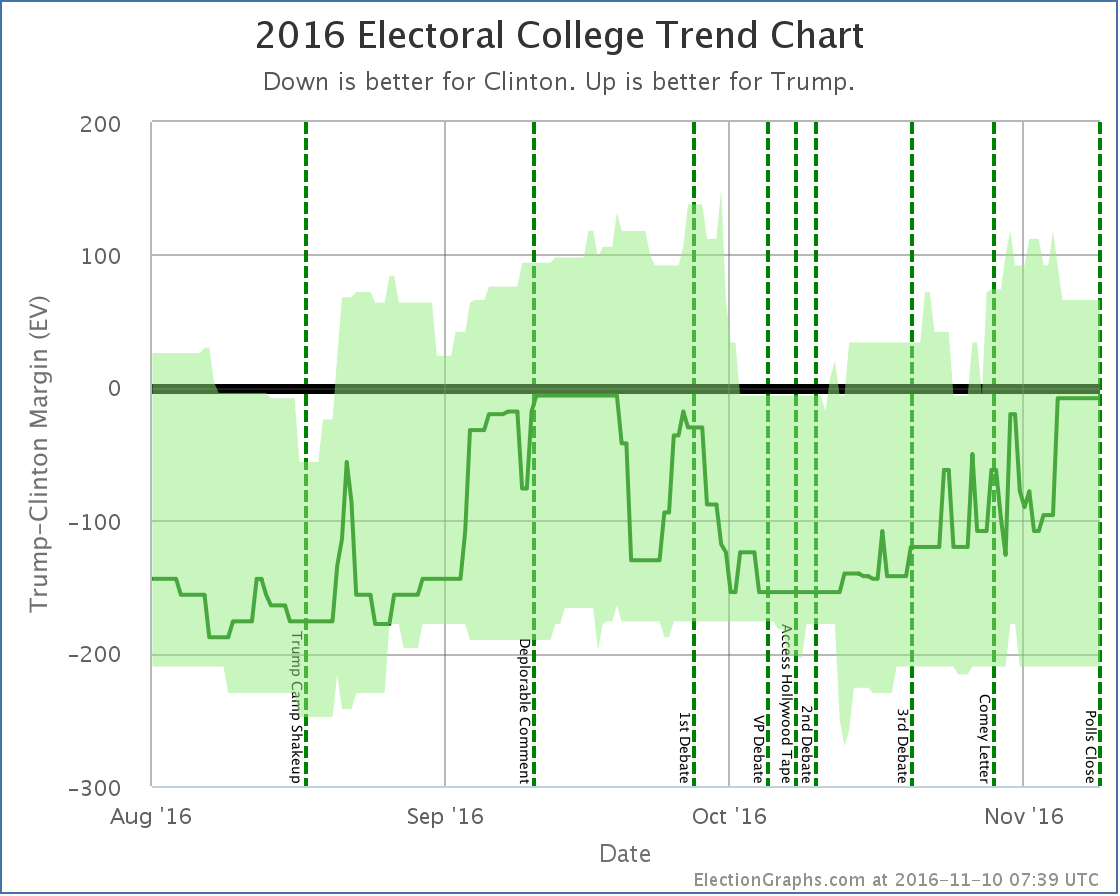

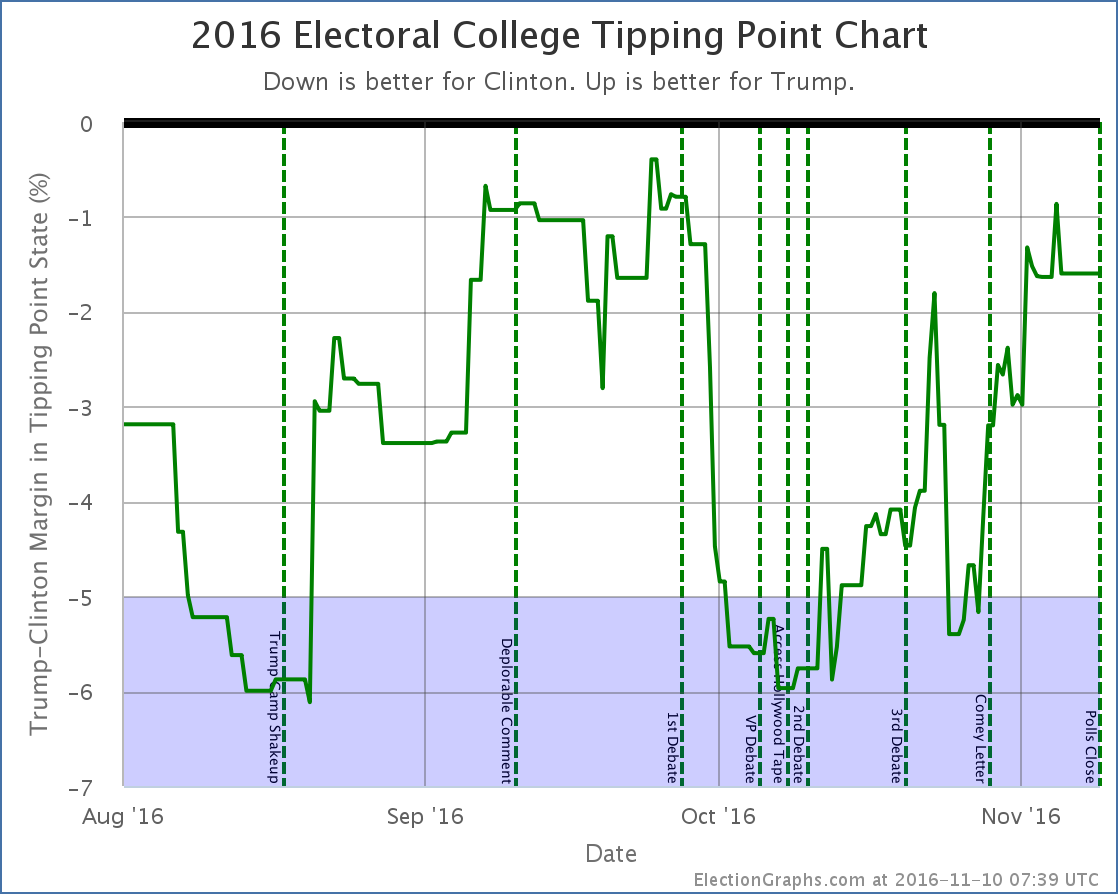

With that in mind, lets look at the two main graphs the site provides once again:

For almost all of the last 100 days of the race, we were in the “could go either way” zone. The exceptions were short periods in August, right around the Access Hollywood tape release, and right before the Comey letter. The rest of the time we had a close race.

Yes, Clinton was ahead the whole time. Yes, Trump had never actually led in my model. But we were within my own self-defined “this is close enough we can’t trust this” margin. This was a close race. And yes, there was a “ceiling” for Trump, but that ceiling was within the margin of error for this kind of model.

I let myself think mostly about the center line of the model, and not as much about the “best cases”. At least toward the end of the campaign cycle. I had convinced myself based on looking at other people’s models that my best cases were probably too extreme. Perhaps useful 6 months out to reflect how much things could change over many months, but certainly too wide in the last couple of weeks or days.

But even if I’d set my thresholds at 2% instead of 5%, my last couple of updates would have shown it too close to call. At 3% it would have been my last three updates. This was close by my own definition of close, and my updates minimized that. They should not have.

And Trump was surging, which brings me to my next lesson:

Don’t call the end of trends too soon

On the Sunday before the election my post was titled “Trump Surge Sputtering Out?“. While the next update did indicate Trump had made the race close again, that was the post full of caveats about how I didn’t really believe the data.

The “looks like Trump has topped out” call was indeed premature. There was indeed mixed data. Clinton was improving on some metrics. But all within the realm that could have been noise. The overall trend was still toward Trump. There was no definitive reversal at that point, as the very next update showed, or would have if I had trusted my own data. If I had, I would have said that last update showed that the trend toward Trump had continued, and had made the race once again very close.

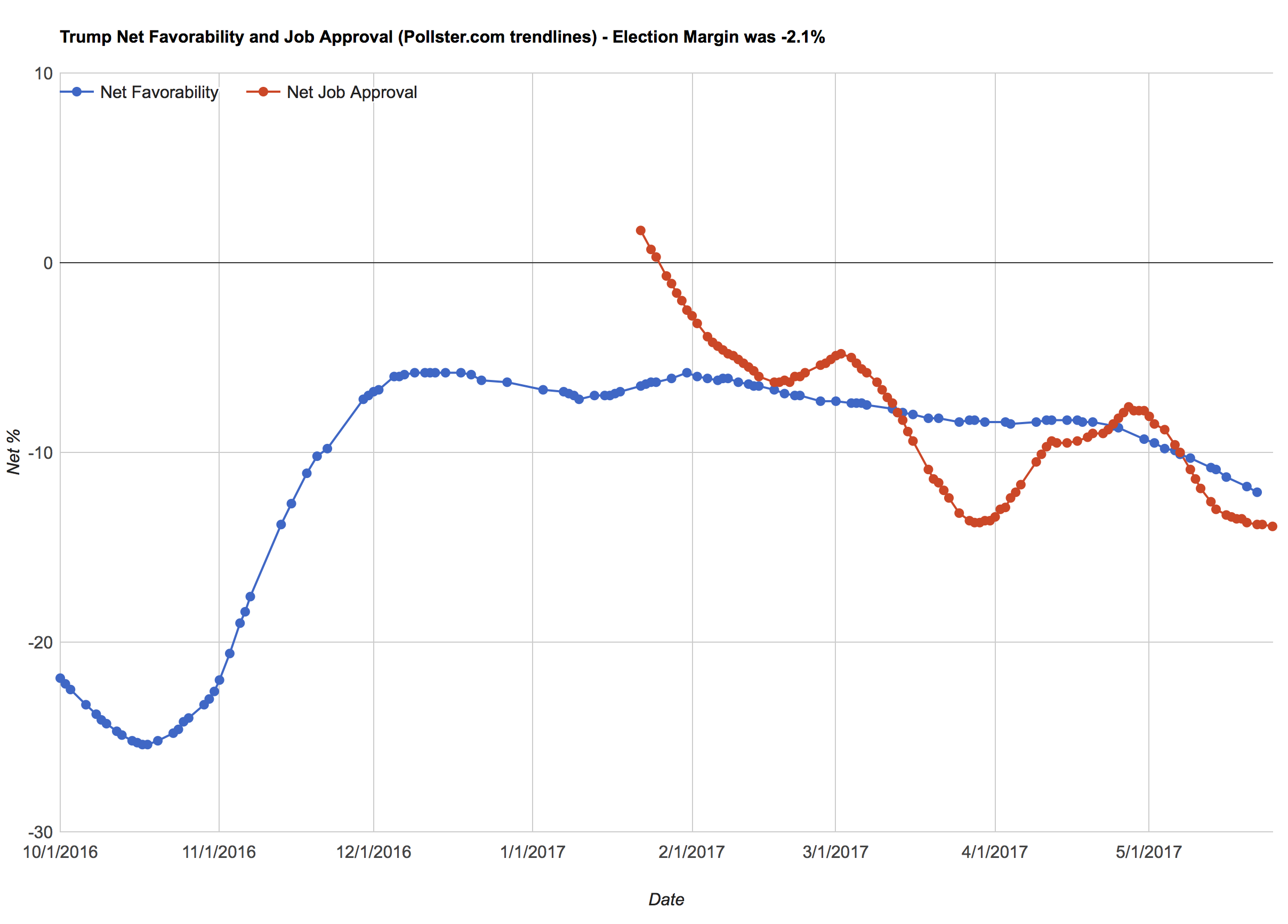

The actual flow of the last 100 days seem really to only have a few phases:

- Before the August Trump campaign shakeup, Trump was in a steady decline

- After the August shakeup, Trump maintained discipline and made it very close by late September (or possibly he was leading if the same polling errors that existed at the end of the race were present then too).

- The first debate caused Trump to crater. Clinton’s margin grew rapidly.

- Trump started recovering almost exactly when the Access Hollywood tapes came out. Far from hurting him, the media pile on about how this was probably the end of Trump’s campaign seems if anything to have rallied people to him.

- After the third debate, there is evidence that people were starting to move away from Trump again, his “best case” was once again a loss. But this didn’t last long.

- After the Comey letter the movement toward Trump (or away from Clinton) resumed. This trend continued up until the last pre-election polls.

In between those there was a bunch of movement, and I pointed out some of them as trends. Many were noise. When you are looking at a jaggy signal full of noise, it is hard to determine where to start saying something is a real trend rather than random movement. Maybe even the trends I called out above are illusions. But it is clear I should have been more conservative in calling out trends before they were dramatic enough to know with a decent amount of certainty that they were not just noise.

Don’t assume trends will continue either

Near the bottom of the trend that started with the 1st debate and ended with the Access Hollywood tape I said this on October 14th:

There is no time left for a Trump comeback from behind win from these levels. It would take something massive that would completely reverse everything we know about this race so far. It would be an unprecedented reversal. Impossible? No. Incredibly unlikely? Yes.

A few weeks ago Trump had managed to make this race close. But it was short-lived. Starting with the debate he has been dropping steadily. We don’t yet have signs that we have hit bottom either. There have been new negative stories about Trump almost every day. Further drops would not be surprising.

We’re no longer really talking about who will win this election. Clinton will win this election. The only question is by how much.

Now, it WAS the biggest comeback in the history of American presidential races in terms of how different the outcome was compared to polling at that time given how little time was left. And I had caveats that it wasn’t impossible. But still, that last paragraph completely dismissing the possibility of a Trump comeback was flat out wrong. It was clearly putting way too much stock in the trend at that moment, and not taking into consideration how little it would take to put Trump’s best case back into the win column.

Indeed, at the time of the comment we’d just seen polls move just about 6% in Clinton’s direction in just a couple of weeks, showing that rapid movement in the polls was very possible. There was plenty of volatility. Plenty of room for movement. A 6% move in the opposite direction in the 26 remaining days should not have been dismissed out of hand.

Save the “it is over” comments until it is actually over. Things can change a lot in just a small amount of time if the right things happen in the course of a campaign. And they did.

Other lessons

I think those were the main lessons, but there were a few others too that will also inform my choices going forward for 2020.

- Showing polls at their mid-point: This cycle I used the midpoint of the time in the field of polls for both determining which polls to include in an average, and showing them on the state detail graphs. This means that if there is a change caused by a news event, the change should be CENTERED on the event rather than START at the event. It means that the movement caused by an event often starts on the chart prior to the event itself. How much so depends on the lengths of the polls that were in the field at the time. Although there are good reasons I thought this was better, it ended up being confusing, even for me. Several times during the cycle I said things like “but this change started before event X”. Some of those (but not all) were just me misreading the graph because of this confusion. Putting all polls at their end date would ensure that any influence from an event would always only show on the part of the charts after that event. (There are down sides to this as well, but it might be better on balance.)

- Third Parties: Although he faded in the last weeks, for awhile McMullin was getting lots of individual polls showing him in 2nd place, or even 1st place in Utah. Johnson came in 2nd in two other individual polls in some states earlier in the cycle as well. The way my site is currently structured, it does not deal properly with 3rd party candidates who are actually doing strongly enough to have a shot at 2nd place or better. I had a high level plan in my head (but nowhere else) for how to revamp my site to deal with this situation, but by the time McMullin surged it was too late to implement it. This may or may not end up mattering in 2020, but I should adjust the site so it can handle these situations from the beginning, so if it does arise, I don’t end up scrambling to deal with it.

- Concentration on the margin: Everything on Election Graphs presents things in terms of the Republican minus Democrat margin. Not only does this break down in the 3rd party case mentioned above, but it also fails to give any way to represent how big the undecided group is and how that might matter. It also can’t differentiate between one candidate gaining, and the other losing ground. Both show up similarly in the margin, but the interpretation for what is happening in the race is different. I think the margin view is very useful, but there is a need to also see the lines for the individual candidates, so I should consider showing that as well.

- Outliers: There were persistent outliers from some pollsters. The case that comes most easily to mind is Google Consumer Surveys persistently saying that Clinton had not just a lead but a big lead… in Kansas. This was ridiculous, and luckily most of the time there were enough other polls in Kansas to keep me from constantly saying Kansas was a possible Clinton pick up. I only said that a couple times, and each time I noted that I didn’t believe it. But it always made Kansas look closer than it really was. Even without the Kansas case, outliers introduced volatility where there wasn’t any in a variety of states, or pushed the average in one direction or another. I need a better way to minimize the impact of outliers. There are a variety of options. I should look into them.

- Poll Selection: There were a number of cases over the course of the year where there were polls of dubious quality. There was also sometimes a question of “is this a poll, or is it a model?”. Or if a pollster was releasing results selectively to favor one side or the other. This site’s bias is to include as much as possible, so I included almost everything. Next time, I need to have clear written guidelines in advance of what gets included and what does not, and I need to stick to it.

- Tracking Polls: Because I base my averages (usually) on “the last five polls” once certain outlets started releasing polls daily, they have the power to completely take over the averages, especially in lesser polled states. This time around I countered this by including only one poll per week from these tracking polls. This solution is not ideal though, as I am clearly ignoring data that might be useful. I need to come up with a solution that can properly deal with tracking polls, incorporating the data they provide, while not improperly weighting them vs the one off polls.

- Data acquisition: My data acquisition process is manual and quite time consuming. It is exhausting physically. I actually kind of enjoy it, but the raw amount of time it consumes, especially in the last few weeks before the election, are disruptive to the rest of my life and unsustainable. It was hard to keep up. Especially with the proliferation of 50 state polls toward the end. At times I was extremely frustrated when I knew certain polls were released, but I didn’t get them incorporated for a day or two, on occasion even three days. I want to be as up to date as possible, and that requires more automation. I have been reluctant to cede control over poll selection by relying exclusively on the data feeds from one of the big poll trackers that provide an API, but I may have no other option for 2020. (Also, at least for 2016, it seemed that I was up and running with my 2016 poll tracking months before those other trackers had 2016 listings up on their sites, although maybe their APIs were already returning the raw data, I don’t know.)

- What to include in average: I like the simplicity of “last five polls” (even with the exceptions I carve out for that). But there is an argument that in the early parts of a campaign it includes too much, and in the latter parts too little. Five polls leaves a lot of room for a single poll to have a big influence. In addition to poll selection questions noted above, the question of how to construct the average itself matters. 5 polls? 10 polls? Some sort of weighting that decays over time? For any day just show the average based on polls actually in the field that day? (You’d still need logic to give a value when no polls were in the field.) If I open the door to weighting the polls, do I weight on other things? Sample size? Previous accuracy of the pollster? This would be throwing out the “keep it simple” tenet of Election Graphs. I already added some of this with weighting multiple results from single pollsters. But is there more I could or should do that would improve things without making the math completely inscrutable to all but the most interested? Or is the site already there actually? I’ve had multiple people say they don’t understand the charts at all. Should I even care about keeping it simple? Or should I just feel free to add all the complications I think would improve the result? Or is all that just tinkering around the edges without actually making an improvement, and 5 polls is just fine…

- Odds: With a race that is close like this one, everybody started looking at the “% chance of winning” not just the expected electoral college results. This is understandable. My model provides absolutely nothing along those lines at the moment. The accurate interpretation of my model would have just been “Sorry, can’t tell you who will win, too close to call!” for most of the last 100 days. To do odds right, I would have to do a real simulation of some sort, like many other people do. But many other people already do that, and do it well. What would I add? I could fake a “percentage chance” based on the model I do have. I could just give what percentage of the “bubble” between the two best cases had each candidate winning. In the case of my final data for this election, that would have shown a 76.1% chance of a Clinton win and a 23.9% chance of a Trump win. That would have put me in between the percentages FiveThirtyEight and ElectionBettingOdds were giving. Of course it would not actually be “odds” in the mathematical sense. It was not calculated in a way that should be called odds. But it is a percentage. And people would probably interpret it as odds. It would also be quite volatile. On the Sunday before the election I would actually have had Trump’s “odds” even higher at 34.8%. A couple weeks earlier I would have had Trump at 0%. People seem to really like having a “% to win” number, I do too. But would putting a number like this just be completely misleading?

Conclusions

It would have been nice to get 56/56 again. But none of the election trackers that I follow did, and my final results were actually better than all but one of them. So on the whole, I think 2016 came off about as good as it could have given that everybody shared the same underlying data. From what I understand, even Trump’s internal polling predicted he would lose, and his win was a surprise to his own team.

So I did pretty well, and I had fun. And really, I do it because it is fun for me. This site does not make me money, it costs me money. And time. Lots of time. So it is important that I have fun with it, and I did.

Thank You

But also thank you to all the people out there who have been following me.

This site does not have the traffic of the “big guys” of course, but there were still a bunch of you out there.

Page views for the site (including both ElectionGraphs.com proper and abulsme.com where these blog posts live) peaked at 23,097 on November 8th (UTC). Unique visitors peaked on November 9th (UTC) at 11,268. And although a few have dropped off since the election, we peaked at 2,334 likes on the Facebook page, 215 followers of the low-volume summary only @ElectionGraphs twitter account, and 405 followers of the @ElecCollPolls twitter account that tweeted out every single new poll as I added them. There were even six people who donated money to the cause through my tip jar in the time since I added it a number of months ago.

A few of you have also made it over to the current events podcast Curmudgeon’s Corner podcast which I do with my cohost Ivan. If you haven’t, check it out. It is more of an opinionated discussion rather than the kind of straight “here are the facts” kind of analysis here, but we think it is fun and interesting too.

These numbers are big for me, but very small compared to the professionals who do this, or even some of the other amateurs.

None the less, while of course there have been trolls saying my analysis was bought and paid for by Clinton or that the numbers were made up, or whatever, there have also been quite a few people who have written in or left comments to say they really appreciate the site, or who have engaged with me in substantive discussion on the analysis or methods. I really appreciate this positive engagement.

I am so glad that the site was useful and interesting to you in this election season. It makes the time and effort I spent much more rewarding than if I was simply putting this out there and nobody was looking.

And of course thank you to my wife Brandy, daughter Amy, and son Alex for putting up with the many, many hours of my time that this has taken up over the last two years, and especially the last 9 months, that I probably should have been spending with them. I appreciate it so much.

One last time to everybody… Thank you!

There will probably be one last post in December after the electoral college meets to report on the actual official results, including faithless electors if there are any. And maybe a post looking at actual state margins vs the last polling averages in each state sometime before that.

But other than those, Election Graphs will now go dormant for awhile. We’ll see you again for real once we start seeing polls for 2020!

1,436.7 days until polls close on Election day 2020. Stay tuned!